The incentive problem

Why social media failed

The landscape of social media held the promise of connecting people from around the world. Unfortunately, this dream was lost as platforms focused on short-term engagement over long-term satisfaction.

Moreover, it was also a race to the bottom, as online there is no real accountability. In physical life, if we injure someone, mock someone, or do something foolish, we face the immediate consequences and have to live with those we hurt. We also have to see their facial expressions, which we naturally reciprocate, causing us to feel their pain, dampening the worst of our extremes.

Online, we have no true accountability and no context in which we have to continue to live with those who we hurt.

The problem of depth

Human relationships are the most beneficial the longer they last. Dating is exciting but the benefits of sharing a life with someone are enormous. To share a life with someone is deeply sacrificial and the effort put in to repair and rebuild a relationship over and over again is significant.

It's the same way with friendships. Having short-term friends who don't know you well, can make you feel part of a group. But the best friends will stand with you for a lifetime. However, it's inevitable that we will offend our friends and that a time of healing, rebuilding and repairing will be necessary.

Online it's much more tempting to cut people off than to invest deeply in relationships. To go from short-term satisfaction to short-term satisfaction rather than invest deeply in people.

This incentive structure leads to weak direct relationships but also weak relationships to a society that could propel and empower a person. The fundamentals of augmented reality-based society will see a similar defective incentive structure. In a world where we're free to go by any username and any avatar, it will be easier to trade horses than to stick it out.

Game theory

In digital spaces, where identities and usernames change and consequences are minimal, game theory helps explain why people often prioritize short-term gains over long-term relationships.

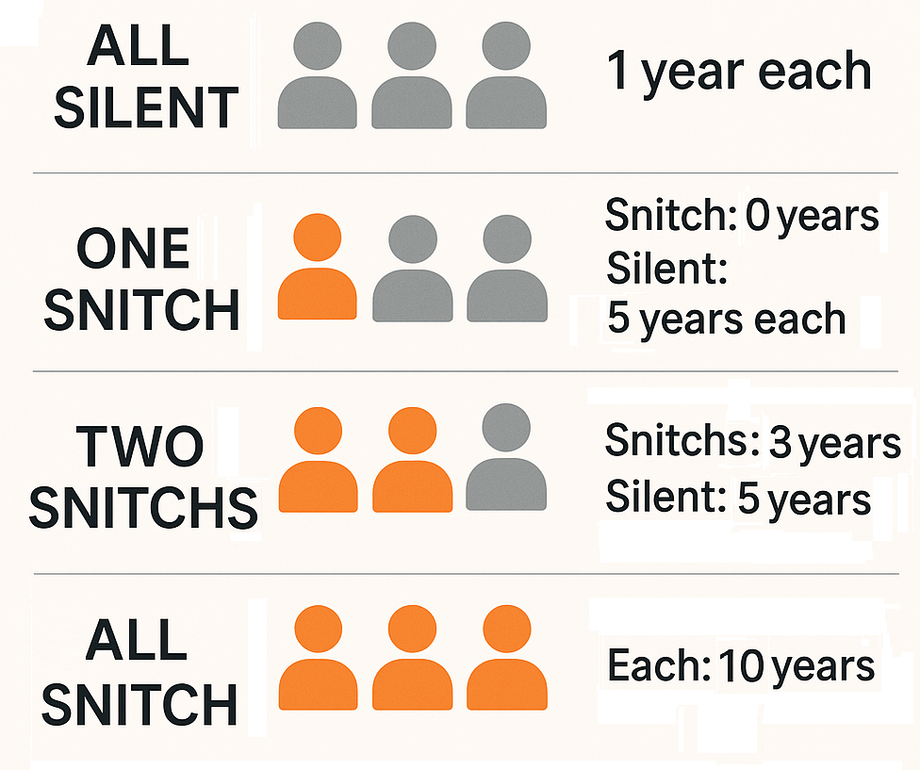

Game theory can be illustrated through the classic Prisoner's Dilemma, a scenario where individuals must choose between cooperation and betrayal, often with self-interest leading to worse outcomes for all.

An overly simplified illustration of the prisoner's dilemma for quick reference.

Full example

Imagine four witnesses, Witness 1, Witness 2, Witness 3, and Witness 4, who are all involved in a crime and being interrogated separately by the police. Each has two options: snitch, betray the others, or stay silent, cooperate with them.

Here’s how their choices play out:

If all four stay silent – There isn’t enough evidence to convict, so each gets a minor charge (e.g., 1 year in prison).

If one snitches while the others stay silent – The snitch walks free, while the three others get the maximum sentence (e.g., 10 years each).

If two snitch and two stay silent – The two who snitch get reduced sentences (e.g., 3 years each), while the two who stayed silent get the maximum sentence (10 years each).

If three snitch and one stays silent – The three who snitched get even lighter sentences (e.g., 2 years each), while the silent one takes the full punishment (15 years).

If all four snitch – They all get moderate sentences (e.g., 5 years each) since their testimonies cancel each other out.

This dilemma demonstrates the tension between short-term individual benefit, snitching, and long-term mutual trust, staying silent. In theory, staying silent would lead to the best collective outcome, but self-preservation instincts make betrayal tempting.

More often than not, in virtual spaces, people consistently choose options which lead to short term gains at the expense of long-term success, for example, laughing at somebody making a mistake, rather than encouraging them. The lack of accountability brings out the worst in human behavior as we see on social media today.

Those who play competitive online games will tell you that this is exactly why gamers are increasingly choosing to turn off their voice chat.

The need for a reputation system

Digital spaces are so dysfunctional for deep community that online reputation systems are absolutely necessary for the humanization of an online space. Without accountability and without a deep incentive to cooperate, digital spaces are a realm of chaos. Unfortunately, online reputation systems are also the potential underpinnings of a digital police state.

As augmented reality brings a sense of depth and reality to virtual spaces, we must be ready for a world that cries out at the awful deeds of people on the internet and calls for levels of control and censorship.

Whereas these reputation systems may be empowering in the context of niche communities we consent to, if they are allowed to leak from one community to another and morph themselves into a global reputation system, it would be to the great detriment of humanity. We at Boundless believe that any sort of global negative reputation system is a recipe for a global digital police state.

Such digital censorship always begins by calling out the deeds of the most evil people on the internet, pornography, child abuse, etc. But from there it spreads from just those people to all of us.

To protect a world in which people are free to be themselves online, a world where people can't harm each other like physical life...

We strongly oppose:

The need for personal identification to use the internet by national government

Negative global reputations that follow people from community to community

Any contract that creates friction when moving from one online community to another.